2020 was the year I moved back to the South West after a brief spell in Norfolk – although to my mind it felt less like moving and and more like running back for forgiveness, as a person might into the arms of a lover whose finer points they had taken for granted. I carried out the move during the height of the first Covid lockdown, half a dozen journeys there and back, across almost the entire width of the country. What I remember most clearly about the days that followed such an insane undertaking is not exhaustion but elation at how intoxicating and fresh and moist the air of Dartmoor’s southern apron seemed, in contrast to the Norwich suburbs, how loud the birdsong was and how empty the lanes were. That May and June I heard more cuckoos than I’d heard since childhood. Not much over a mile from my front door I chanced upon a deep pool to swim in under a bridge on a lane to nowhere commercial. As it turned out, due to the structural condition of the house I’d moved to, the grasping unsympathetic behaviour of my landlords and two extremely horrid and surely not unrelated bouts of illness, I was about to experience the most dramatic late summer comedown of my life and need to move again, only seven months later. But for the time being I was on cloud nine, exploring on foot every publicly accessible part – and a few non-publicly accessible parts – of the nearby landscape that I could. The village I had moved to was called North Huish. “Huish” comes from the West Saxon word for “household” and I intended to set up my own here, for a long long time, the fact that I was merely a tenant notwithstanding.

I immediately went hard to work on bringing some wild order to the house’s beautiful but long-neglected walled garden. Several carloads of old plastic bags and obscure lengths of rusty metal and broken glass were taken to the Recycling Centre. Years of brambles were hacked back. I planted kale, artichokes, lettuce, corn, courgettes, cucumber, broccoli. Being at the bottom of the steep valley felt like being in a giant open-topped cathedral where blackbirds were the choir. I shared my bedroom wall with a family of mason bees. I told the window cleaner not to clean the window on that side, as I liked the bees and didn’t want them to get wet. I was infinitely fascinated with the garden wall and began to notice other old walls even more than I had previously, which had already been quite a lot, and get pulled into the complete moss and lichen galaxy that they irrefutably were.

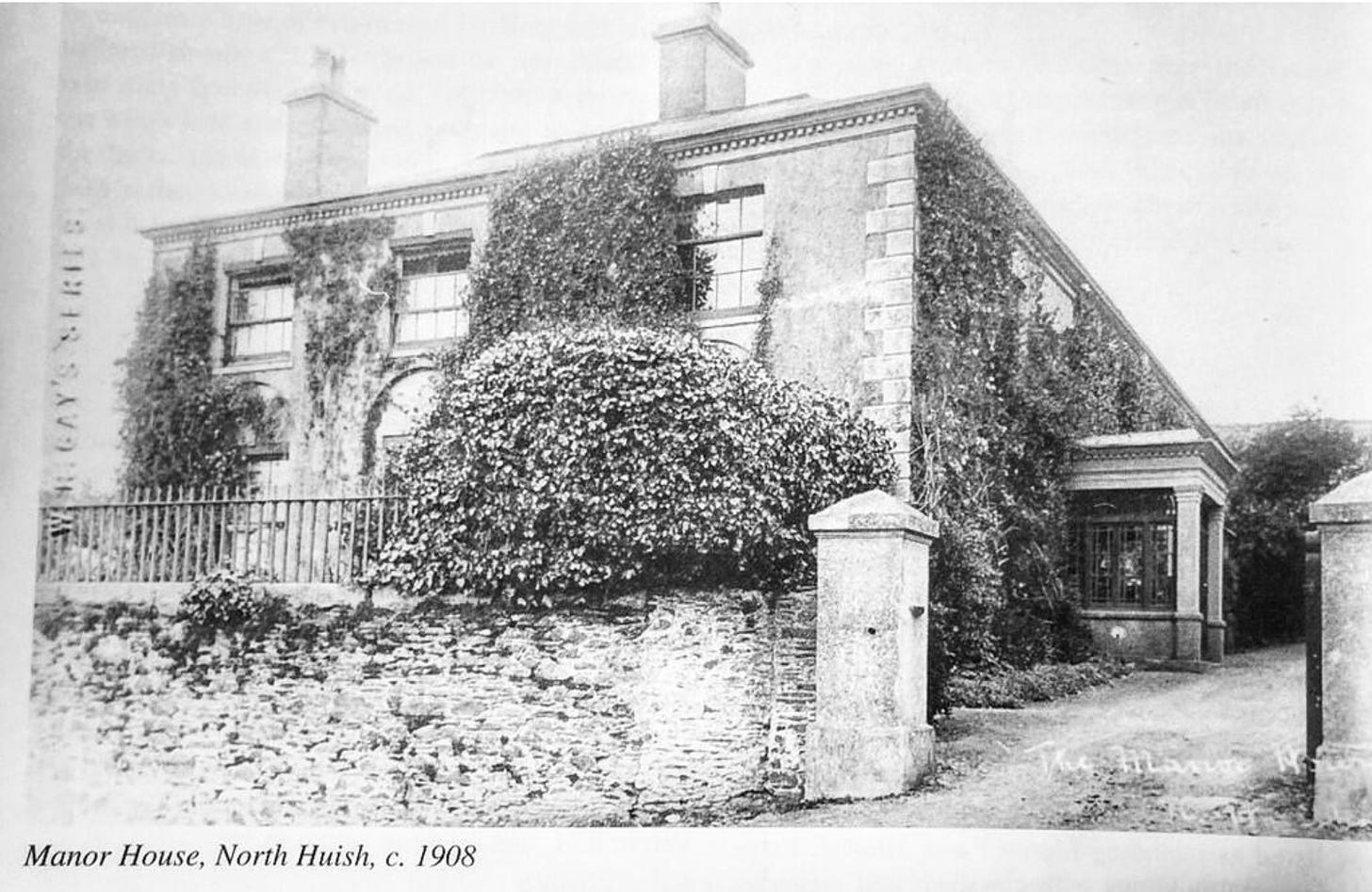

At the top of the natural cathedral was where the jackdaws lived: mostly around the village’s beautiful 15th Century church, out of use since the early 1990s but wonderfully preserved by the Churches Conservation Trust with, by the time of year we have now again reached, red Valerian exploding from its granite walls. Next-door to this was a huge old house with another walled garden – dark grey, known as The Manor – which I felt powerfully drawn to every time I walked past it, usually on my way to buy eggs from the honesty box at the top of the hill, swim in the river or stroke the chin of a sheep in a field further along the lane who I suspected was in fact an undercover panda.

The Manor’s windows had an intense black magnetism to them and, from the collapsing, scaffolded state of the building’s west side, many people might have been sceptical about its habitability. Yet something made me feel that there was someone living inside it who I would like to get to know. I almost knocked on the door and introduced myself as a new neighbour a couple of times but the pandemic had recently hit: people were keeping a strict distance from one another. Sadly I will never get that opportunity again, since the Manor’s owner, an antiquarian book collector, died last December, at the age of 94.

The Manor had been built at the very beginning of the 19th Century, on the site of a much earlier manor house, and was in quite a severe state of disrepair when The Collector and his Danish wife purchased it at the end of the 1950s. At this time The Collector was a Lieutenant Commander in The Royal Navy. After the couple had completed its restoration, it became a much-loved gathering place for their extended family along with, according to The Collector’s niece Jane, “waifs and strays” The Collector took “under his wing and installed in tents or the garden, often to the dismay of my aunt, who was expected to feed them.” Jane and her sister would stay there often, exploring the old servants’ quarters and imagining the life of the house in the previous century, hiding behind fur coats and naval attire in wardrobes, scaring themselves by looking for the cowled ghostly monks their aunt had told them about, or reading on an old naval hammock slung between two trees in the garden.

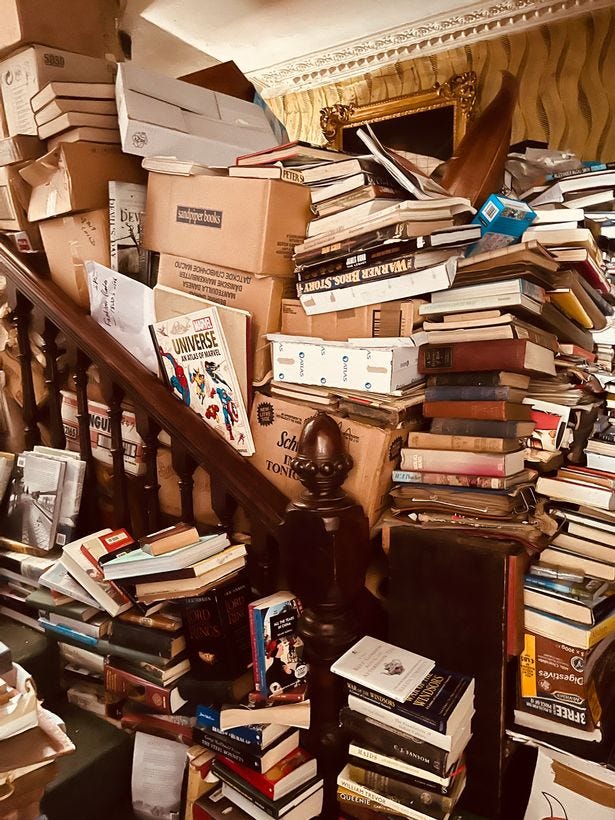

By 1986, when his wife died, The Collector had long since given up the navy for the career he truly desired, buying and selling old books. Soon, a staggering number of volumes began to swamp every room in the house, smothering furniture and blocking the entrances to rooms. Eventually there was nowhere left for The Collector to sit in his own vast house and read other than a tiny stool in his kitchen and the small part of his bed that wasn’t covered in books. After his death, the Torquay-based house clearance firm Grab It was brought in to clear around 30 tonnes of possessions from the house, much of which was literature. It turned out to be their biggest ever job, taking four men a total of eight days to complete the work. Yet still many books remained. Numerous piles could not be moved, as it was feared that they were all that was holding parts of the house’s structure together.

On Wednesday this week, I was fortunate enough to finally visit the Manor. I was entirely unprepared for the emotional suckerpunch I received upon seeing this previously secret compartment of the natural cathedral where I used to live, the same cathedral on whose bottom floor, precisely three years ago, I’d placed my own ever-expanding book collection, then dug deep into the soil and tried in vain to make a permanent and still life for myself. It was a perfect day, cloudless, warm but not too warm – the weather my memory has tricked me into believing was unbroken for the first three months I lived there – and an apt day for seeing the Manor, which, behind its daunting dark stone facade, is surprisingly bright and sweet, like a vast sepulchre filled with honey. If there were ghosts there, I sensed they were happy ones. The sun streamed into the garden, which is currently a wildflower meadow at its apex, and I imagined the people who once camped there. 1968. Kaftans. Books on mysticism. A bonfire. The air alive with conversations about ideas and art. Guitars. Perhaps the legendary cult songwriter RJ McKendree turned up. He was, it is rumoured, not far at all from the area at that exact time.

Maybe unsurprisingly, given his approach to domestic order in the later part of his life, The Collector possessed no less of a gift for losing things than he did for collecting them: house keys, car keys, spectacles, hearing aids. When he did, there were plenty of people on hand to help. He was well-loved locally, a church warden and member of the Parish Council who drove elderly neighbours into Totnes, eight miles away, so they could do their shopping. He collected people, as well as books, but in a fascinated, kind way, not in a cynical way. He was often seen walking the lanes of Huish and Avonwick with one of his cats, most of which he simply called Cat. During these occasions he would always be immaculately dressed in a tweed jacket, shirt, tie and brogues. Chaos increasingly reigned inside the manor but outside its doors order was maintained, as was a driving licence and a long term relationship with a lady who lived a couple of hours away in the city of Bath. He loved seeing her but also loved being back at home, with his books. The house began to crumble. Nobody but bats had been in the old servants’ quarters for decades. He was determined not to budge. “I’m going down with the ship,” he told his nieces.

As I climb the walnut staircase to the upstairs rooms, I swirl and spin in time and sunlight. I’ve now left 1968. I’m somewhere much further back, long before The Collector’s time, watching the extraordinary Victorian wallpaper being attached to the walls of the second bedroom. Much of it has survived. Obscuring some of it is art by The Collector’s mother-in-law, a Danish heiress who roamed the world painting after her husband stole her inheritance and vanished without a trace. The Collector’s ghost watches me as I cross the hallway. “That hard hat they’ve made you wear is a truly hysterical precaution and doesn’t suit you at all,” he says. “I know you want to get over there to those books, to see if there are any obscure ones on folklore, but I can’t recommend it. The ceiling might fall in, although who can say with any certainty? I haven’t been over there since John Major was in power.”

“Hoarder Passes Away” said the headline in the local media when The Collector died. They saw and used the pictures, the ones of the books blocking the hallways, but neglected to see or paint the bigger one. They never imagined the young man who, alongside his partner, restored a crumbling house then had the pleasure of living in it, enjoying its atmosphere, and inviting countless others to join him, for many years. “Hoarding is an illness,” responded the below-the-line keyboard warriors. Had they ever known the joy of surrounding yourself with love and knowledge and learning? What exactly was the more socially acceptable way to live out your final years that they would recommend: the one where a person does everything cleanly and neatly and correctly in the eyes of society, right until their final breath? Does it even exist? And if it does, does it make anyone who achieves it better, or happier, in their last years on the planet?

It’s the main bedroom where I can feel his presence the most. That’s the one point where I feel it’s a bit too intimate, me being here, any stranger being here. There’s a lone naval jacket hanging in the wardrobe and a huge chunk of ceiling hanging loose, like a loft hatch fashioned in an emergency by an unusually strong person. On the mantlepiece is a picture of The Collector’s uncle, who died in World War One. I stand beside a dusty chaise longue and admire the view across the valley, trying to work out where the part of the River Avon that I walked along earlier in the afternoon is. There’s a tributary down there I always used to want to follow in 2020 but couldn’t work out how to: a chunk of clandestine countryside, tantalisingly unexplored. This is a special room in a special place and this whole experience is about the past but this moment, right now, feels like something to savour. Today is one of the final days when this room will ever look like this: soon someone who makes a successful bid in an auction room next week will empty and transform it, hopefully not without sympathy for all the people who have slept in it.

And then, maybe because I’m looking down the valley in the direction of my old house, and maybe because early evening is approaching, I remember another evening, around this time of year: I’m living alone, just as I have for several years by this point, and that’s great, even though it won’t be all that long until I’m not any more, and that will be great too. Family and friends who live many counties away express worries about me, living out here in the sticks by myself at this unusually isolating time in world history. I repeatedly tell them the truth, which is that my life had been a bit too hectically sociable just before that and I’m really enjoying reading and gardening and working on my novel without interruptions. On this particular day I’ve been for a swim in the sea, read most of a short Herman Hesse book, and dug out the flower bed in front of the living room. As I continue to dig, I hit something soft but tough, not at all soil-like, with the trowel. I discover that it’s a toad. I apologise to the toad profusely then apologise again and sit on the wall holding it in my gauntlets for a few moments. It seems dazed, but undamaged. The big garden gate is open and I hear footsteps approaching along the lane. A man. Tweed jacket. Old but sprightly. 80ish? Maybe younger. Maybe older. Maybe it isn’t a tweed jacket. Maybe I’ve just made that up. But he was a man. On a walk. Alone. And he wasn’t young. And he seemed like he was wearing a tweed jacket even if he wasn’t.

He stops and glances through the open gate. “Toad?” he asks.

“Yes,” I say. “I hit it by mistake while I was digging. I was a bit worried I hurt it.”

“It will probably be ok,” he says. “They’re resilient fellows. Have you moved in recently?”

“Yes, a couple of months ago.”

We introduce ourselves, from a safe distance. I forget his name four seconds later, just as I always do, unless somebody tells me twice.

Before he strolls on, the stranger points to the toad, who is by now lurching off industriously, attempting to find another shadier spot. “Just wants to get on with being a toad, without being bothered,” he says. “Nothing wrong with that.” I’m not sure if he actually says this but in my memory of the evening he was the kind of person who would say it and I know that, if he did, I would have agreed, because I definitely did.

“No doubt I’ll be seeing you around, then?” says the stranger.

“Yes, definitely,” I say, turning to get back down into the soil, this time a little more tentatively.

You can now subscribe to my Substack page here.

My latest book is called Villager. You can order it here from Blackwells with free worldwide delivery.

Another piece, not dissimilarly themed, that I wrote recently.