Often it’s only upon seeing photographic evidence that you realise just how long you’ve been working on your novel.

This year marks my twentieth anniversary of being a published writer, so I thought it was as good a time as any to jot down some thoughts about what I’ve learned in those years. About a month from now it will be precisely two decades since I sent my self-produced A4 fanzine to the Live Reviews Editor at the NME and he generously commissioned me to drive over some northern hills and review a gig by a band, for actual money. Since then, I’ve had a bumpy sort of ride: the kind potentially experienced if partly taken in a tractor, partly in a quite a nice 1970s Ford Granada with some bits hanging off it and partly on a spavined mule. I’ve wondered on a couple of occasions if I’ll have to give up and do something else, but somehow I’m still here, surviving, and enjoying it in a new way, feeling more like myself in my writing than ever. I can’t say that the points below are precisely advice; they’re more a bunch of thoughts that have been rattling around my head a lot over the last six months and which I wanted to get down as a record of how I feel right now. They’re intended for me, more than they are for anyone else, but I decided it couldn’t hurt to let others read them too. I should add that they’re more about the stuff surrounding writing than my writing itself, which is increasingly in its own odd little niche: these observations won’t apply to everyone but there are perhaps a few universal points contained within. I’ll probably change my mind about it all again soon, as I often do, so all in all you should probably take it with a pinch of salt. In fact, maybe that’s one important point missing from the list below: Reading Tips About Writing On The Internet Will Not Make You A Better Writer.

Walking Is Writing’s Little-Reported Secret Weapon

It’s no coincidence that the moment my writing took a noticeable leap in the right direction coincided with the moment I started going on a lot of country walks. Some of my pre-walking era writing is decent but I can’t think of one piece or book that doesn’t make me wince at least a tiny bit. All writing would actually be at least twice as good if it was composed during a country walk. The brain fizzes with mysterious energy and inspiration with the benefit of fresh air and pumping blood and world is seen from a less flat and jaded angle. I try to trap the insights and observations I have while walking here in Devon but because I’m 40 now and my brain is decaying, they often escape. This is one of the cruel paradoxes of getting older: you have far better thoughts than you once did but it’s a bit of a moot skill, since you tend to forget them seven seconds later. I wrote a bit more about this subject here.

Find The Weird In The Everyday And Make A Home For It In Your Notebook

My typical way of recording the thoughts I have at the end of a country walk is to find a pub and furiously scribble down every insight and incident I can remember as I down a pint of ale with a fox or a hare on its logo. I’m not sure I have regrets as a writer – the big chaotic mess of all the stuff I’ve done wrong is an important part of the process – but at a push I might concede that one is only making regular notes on my life from 2008 onwards. Sometimes you don’t even have to refer back to something you’ve written in a notebook; the mere act of jotting it down will help you remember it. I’ve trained the part of my memory relating to weird everyday stuff to be pretty sticky – at the undoubted expense of my memory as a normal functioning adult human – but my notebook is where you find the crucial colour: an extra odd detail that might give something an edge. My early non-fiction books, written when I was a less diligent note taker, are severely lacking in that. In my first book, Nice Jumper, for example, I omitted to report the fact that one of the main characters collected hub caps that he found at the side of the road, and that, when ordering chips, another character used to specify the precise number of chips he wanted. I still scold myself about both to this day. I used more poetic license in my early books, whereas my recent ones are entirely as they happened, with the exception of a couple of renamed characters and disguised locations. I think this is indicative of my growing trust in reality to provide me with the goods.

Everyone’s Writing About Themselves To An Extent So Don’t Worry (But Do Also Worry, A Little Bit)

I’m a frustrated fiction writer. I’ve abandoned two novels – probably sensibly, with hindsight. Around eighty percent of what I read is fiction, and I still believe it’s the purest art form. For many years I was furious with myself for not having written one of the several novels that were constantly trying to punch and claw their way out of my skull. Since then I’ve become more comfortable with creative non-fiction, feel less rushed to escape from it, realised it doesn’t have to be as limiting as I once thought. My biggest barrier in creative non-fiction writing is always the same: making myself believe anyone would give a crud about my existence and what little I have to say. What I write tends to be on a small scale: it’s not about huge dramatic adventures or a remarkable life. But for me that’s ok. Most of my favourite books aren’t, either. I remember early on in my writing career being pushed towards far-flung travel writing and gimmicky “mission” projects by a couple of mentors and it took me a while to realise that it wasn’t my thing at all. I gradually came to realise that I’d rather try to write imaginatively about small things than get by writing passably about big things. At the same time, I do think that little sneering voice telling me that my life is too mundane for anybody to be interested in is useful, and I wouldn’t want to be completely without it. Every writer can benefit from a small demon on their shoulder alternately whispering “This is great! This is rubbish!” in their ear, as long as they don’t let it run rampant over their life like a little horned twat.

The Fight For Content Over Theme Is An Important One

During the conception of my first six published books – and several others that never saw the light of day – I asked for far too much advice. I think as much as anything this was about my background and lack of formal education and qualifications: I do not have A-levels, let alone a degree. I would treat my former literary agent and editors – who did have plenty of formal education and were from far posher backgrounds than me – as superior bosses I needed to contact for permission before trying something out. I was more like an orphan pleading meekly for some gruel than anything vaguely resembling an artist, and it never occurred to me that the writers I most admired didn’t do the same thing; they just fucking went for it and believed in themselves. It took me years to get out of that mode, and I think the fact I released myself from it is one of the reasons why my two latest books – and hopefully the one I’m currently working on – are an artistic step up from the six before them and have had a greater resonance with passionate readers, who don’t give one shiny bollock about marketing and boxes. What would happen, invariably, after I’d spoken to an agent or an editor, was I’d generate lots of ideas, and waste time writing proposals for books my heart wasn’t fully in. Ideas are great, and it’s important to have them, but they’re overrated and no substitute for just getting down the stuff you’re burning to say, even if you don’t know where you’ll end up, conceptually speaking. If you’re ardent and loving enough about what you’re doing, a form and concept will emerge soon enough, without you having to be too prescriptive and controlling about it.

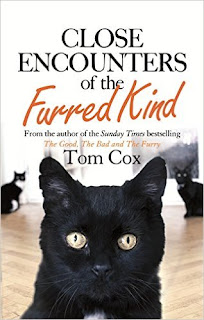

I loathe writing book proposals. I think that, by their very nature, they’re the antithesis of good writing, because when you’re putting them together you have to think like a salesman. It is very telling that my worst book, Educating Peter – a book I now actively encourage people not to waste their time on – made for the most publisher-seducing proposal and the highest advance of my career. Similarly, my biggest regret about my cat books is rolling with the “Confessions Of A Cat Man” schtick for the first one, and changing the intro to play up to it, at the request of my then publishers. It’s true: I am a man, and I like cats, but I think – just like the awful covers that were originally on that and my second cat book – it gives potential readers an impression that they are about to read a different kind of book. It’s entirely understandable that agents and editors want to fit books into boxes but doing the same should never be your job as a writer. The best creative non-fiction – that of David Sedaris, for example – is often the most obtuse, the least marketable, the most uneven and real. Sometimes I feel like my career has been a long struggle to be allowed to write books about nothing. Maybe because books about nothing can potentially be books about everything, too.

Ignorance And Delusion Are Great Assets When Starting Your Career As A Writer

Books made me want to be an author but if at the time I’d had a full sense of just how many great novels and memoirs had been written, just how many supertalented writers had been overlooked and failed to make a living, I wonder if I’d have felt differently. I suppose being a young writer is like being a teenager in this way: an essential part of the fun of it is thinking you’re some kind of revolutionary here on earth to tell a brand new story rather than eventually add your own subtle individual slant on a story that’s already been told a million times. Another essential part of this ignorance is not being realistic about just how long – unless you’re a very unusual case – it’s going to take before you write anything genuinely good (I almost wrote “genuinely of worth” then but I didn’t, because it’s all of worth). This is why I doubt I’ll ever earnestly write one of those “advice to a younger me” pieces. Were I to travel back to this point in 1996 and visit my twenty year-old self and tell him he wouldn’t properly find his voice as a writer for well over a decade, would he be happy? No, he’d probably want to kick me in the nuts and tell me to get bogged. Also, a few people – though very few, and certainly not me – do write great books in their twenties and I think striving to be one of them by writing and reading loads is something to be fiercely encouraged.

Get Ready To Have Lots Of Conversations Where Strangers Totally Misunderstand What You Do For A Living

I’ve noticed that the more the process of writing stimulates me and the more direct my writing becomes, the less graspable as a concept it tends to be to anyone but those who read it. “I write books that are ostensibly about cats but are actually largely just excuses for me to write about landscape and folklore and nature and my loud excitable dad” is not really the answer your postman or someone who’s come to tile your kitchen is looking for when they ask you what you do for a living. In this sense, I probably should have stuck with my job as the Rock Critic for a national newspaper: everyone I met seemed to instantly understand that and view it as a fantasy job – which I certainly did too, for a brief spell. I didn’t want to ruin it for anyone who fetishised it by informing them of the smallprint: that I earned less than I would have if I’d progressed to a low level floor manager job at the supermarket I’d been working at a few years before, for example, or the stunning snobbery and hypocrisy of some (though not all) of the people who employed me, or the fact that music writing is by its very nature less synonymous with quality prose than almost all other forms of writing. I’ve made it even worse for myself now: my giving up journalism last year I lost those logos above my work that, for all its distrust in the media, the outside world still sees as a calling card or seal of approval. Of course, there’s loads of good writing on blogs these days – looser and not shackled by PR schedules and trendy fad cockwaffle in the way its newspaper equivalent is – but to most people blogging is still a dirty word. “I write stuff for my website” is never going to lead to the intrigue and kudos that “I’m a columnist for a national newspaper” or “I’m a music reviewer for a national newspaper” or “I’m a film critic” is but I’ve done all four and I know which one I enjoy more, by roughly six thousand miles. In terms of my books, it would probably be easier if I could tell someone in a soundbite that I did something that fitted into a nice bohemian-sounding literary pigeonhole, but I think almost all of us who just about get by as authors end up being misunderstood, even if it’s only in the sense that people always seem to think we’re either loaded or wonder how we can make any money from what we do at all. This is a version of a conversation I and many others often have, which I have transposed to the world of plumbing:

“So what do you do for a living?”

“I’m a plumber.”

“You mean real, published plumbing?”

“Yep.”

“How many houses have you plumbed?”

“Quite a few now.”

“Real houses?”

“Yeah, with sinks and pipes and stopcocks and everything.”

“I’ve got an idea for some plumbing myself. I expect you have lots of connections. Do you think you could help me find a house to do it in?”

Social Media Can Simultaneously Be Your Asset And Your Nemesis

Facebook and – in particular – Twitter have been a great way for me to reach new readers, but they can be a pain in the arse too. By using the Internet to try to sell enough books to sustain a career you’re also effectively signing a virtual contract that says “In exchange for gaining readers who enjoy my work, I agree to be exposed to the opinions of a vast amount of people who have never read it yet who will make snap judgements about it.” To get a book to its intended audience these days means sending it on a potentially prickly journey past its unintended one. I’m frequently told on the Internet what my books are about by people who have never read them and never will do. But that’s ok. It doesn’t matter, and ultimately – save for all but the most spiteful troll – it tends to fly away on the wind. I don’t like the feeling that I’m annoying anyone on Twitter with what I do and it upsets me that I can’t realistically reply to everyone who tweets something interesting or nice at me, but when social media works, it can offer a way of homing in on a brilliant, understanding audience and bypassing the traditional metropolitan media circle jerk that helps books to sell. You can gain a modicum of strength that you could never have had in the online universe of a decade ago. Obviously, I’d love it if it wasn’t necessary – if writing books was as simple as just writing books then sending them out into the world to survive all on their own – but, like many writers, I have to be realistic about the fact that this is not 1923, or 1968, or even 1989. I tweet a fair bit in the hope that I might soon not have to quite so often: not because doing it is without enjoyment but because when you tweet more often you’re more exposed to that small percentage of bitter, disappointed humanity that crouches obsessively over its device all day in a tight furious ball, getting its sole source of oxygen from knee-jerk pond-skimming hatred and the smattering of virtual back pats that inevitably brings. I know that as a result of my tweets people who’ve never read my books, and never would read my books, might mistake me for something I’m not – sometimes just a person who is far nuttier about cats and far more indolent than I am – but I know that at the same time a minority of new people might take the time to read stuff I’ve written for free on my website and share it, and that is extremely valuable to me. My first six books received a fair bit of media coverage; the next, which I know without a shadow of a doubt is a fair bit better, received almost none; the latest, which I hope is a bit better again, received absolutely zero. It has also not been massively prominent in shops. It has, however, still been fairly widely read, due to the power of reader recommendations.

I’m talking from an individual perspective here, again. Lots of writers love going on TV and are very at home in the newspaper world. I have no interest in going on TV and don’t intend to write so much as a sentence for a newspaper ever again. I’m happy with a small audience, but one which is big enough to keep me writing until I’m too senile to do so any more. If not, I’ll contentedly have a go at something else, as a sideline to my books. Maybe I’ll train as a gardener. I’m always looking for excuses to be outdoors more. But I will still write. I’ll have to. That’s the thing with writing: you have to accept that once you’ve done it for a while it will become another integral part of you like lust or an elbow.

The Longer You Go On Writing, The More ‘Improving’ Becomes About Knowing What To Leave Out

I had very little of interest to say about the world when I first started receiving small amounts of money in exchange for my writing. I was 20 and had grown up in various fairly culturally segregated parts of North Nottinghamshire. All the stuff that most interested me was three or four solar systems away from my actual life. In a way, I was lucky to find stuff to write about at all. I was probably mostly just filling space and learning to express myself less awkwardly. For a period after that, I improved by discovering what it was I wanted to say and how best to convey it. But most of my improvements as a writer since then have been about learning what to leave out. When I look back and wince at my earlier writing, it’s sometimes because I left out something vital, but far more often it’s because I’m looking at a joke or an observation and thinking “That was unnecessary.” Looking back, I don’t recognise the unenthusiastic chiseller who groaned at editing time early on in my writing career. I relish editing now, but I think a love of editing is something that usually has to be learned. Being edited by someone as talented as ex-Yellow Jersey Press Director Tristan Jones, who was more brutal with the first draft of my second golf book than anyone has been with a piece of my writing before or since, certainly helped me become a lot harder on myself. These days that feeling of tightening screws at editing time – “Surely that’s tight enough!” “No! Give it another twist!” – is almost as pleasurable to me as the first rush of inspiration upon starting a new piece of work.

Be Okay With The Fact That Most People Won’t Understand Your Reading Habits

My choice of reading is possibly the area of my life where I’m the biggest snob. Not in the sense of “I only read highbrow literature.” I’m just incredibly picky because I want everything I read to be a perfect balance of enjoyment and brainfood: I want to read for fun but I also want to read to expand my own range as a writer. Fortunately these two goals fit together quite well on the whole, but they do mean that I’ll often opt not to read a book on a familiar subject which looks like it will be perfectly fine, or a book the universe is raving about. And while most of my reading is chosen on recommendations by knowledgeable, excitable friends and acquaintances (always a much more reliable source than book reviews in newspapers and magazines) I don’t borrow books because my own gigantic to-read pile already scowls at me judgementally enough and I’d rather not add to it the worry that I haven’t read and returned somebody else’s book. I’ve become better at jettisoning books I thought were okay but I couldn’t conceive of abandoning any book I’ve loved: they’re so much part of who I am, as a person and as an author. It could be argued that what you are as a writer is the sum of your experiences, your hopes and your disappointments, plus the books you’ve read. It can take a long time for this to coalesce into an individual voice, though. If you’re getting antsy about it, it’s hard not to look at the life of musicians slightly jealously. They can take a fair while to find their voice too, but at least listening to records is quicker than reading books. Songs, unlike books, can be written in a day.

I’m naturally a fairly impatient person, which – along with the fact I lack the necessary skills to be a proper hermit – is one of the ways in which I’m less qualified than I could be to write for a living. Even as someone like me, though, one day, after many years – even if you’ve been too easily distracted from your goals too often, farted around with too many projects that weren’t what you had your heart in, not read anything like as many books as you’d planned to – you might wake up and say, “Actually I have read quite a few books now and written a fairly sizeable shitload of words in my life and seem to be saying at least some of the stuff I always intended to.” I know my first literary agent would have loved it if I’d been huge when he signed me up, back when I was 25 and a little prettier than I am now, but at the time I hadn’t read or written or lived enough and, besides, I’m not a writer who desires to be huge. I desire, chiefly, to be have the freedom to continue to write the stuff most true to myself. The process reminds me a little of a line in Margery Williams’ The Velveteen Rabbit about being real: “Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off and your eyes don’t see as well and you get loose in the joints and very shabby.” In a way, writing books is a bit like being the Velveteen Rabbit. It’s a bit of a bugger, but the fact is that you usually have to wait a fair bit of time before you become real.

Read my latest book which sort of is about cats but sort of isn’t at all but still sort of is but still sort of isn’t at all.

Tom, you are immensely talented. You write with such warmth but not necessarily for your subject, it is the love for the very act of writing in and of itself that shines through in your work. You have an uncanny skill for observation, you take the mundane and familiar and make it entertaining and your ability with characterisation really is sublime.

I first found your work when I was bought a copy of Under The Paw. I have cats, I like cats but had never read a book with a cat on the cover, assuming them all to be twee. This was so not the case! I have since read all your books, and there is a definite evolution occurring in your style. Please continue to write, I don't care about what, just write please. 🙂

I'm glad you write.

This is another great piece (I'm sure a lot of us think it's easy doing what you do because you make it look so easy Tom). You write in a quietly mesmerizing style – it's not formulaic, there are no tricks or bells & whistles but you serve up the perfect 'double shot of life with a twist' each and every time! It's lovely infectious stuff. We'll keep you stocked in pens and notebooks if it'll ensure you keep on writing!

This is another great piece (I'm sure a lot of us think it's easy doing what you do because you make it look so easy Tom). You write in a quietly mesmerizing style – it's not formulaic, there are no tricks or bells & whistles but you serve up the perfect 'double shot of life with a twist' each and every time – it's lovely infectious stuff. We'll keep you stocked in truckloads of pens and notebooks if it'll ensure you keep on writing.

A question I can now ask myself – have I reached The Velveteen Rabbit stage?! As ever you come up with expressions and observations which make me think, and smile. Don't despair about using the 'cat man' label to entice readers in your earlier career, it piqued my interest and got me buying the books, and then I was surprised that so much of them was about other stuff. And now your website /blog seems to have a life of its own.

Must go – I've been up since five!

I would suggest rather than gardening (having been a gardener) which you might find drives you round the bend with too much primping and neatness, you might like being a warden or ranger. Very land-focused with a real sense of looking after a place. Your writing has improved, you're right, keep going. It is inspirational, moving and informative; which is really all that is needed.

Well I am very excited about finding your blog Tom. An on-line friend recommended it as she knows I like to write but also that I struggle with confidence. You certainly pushed a few buttons with this article but in a good way. I'm looking forward to doing a lot of catching up with your work and hopefully learning a thing or two in the process. Thank you.

I really enjoy your writing, whether it's one of your books, a tweet, or an essay on your blog. Twitter is how I first found your writing. Even when I'm in a hurry and skip a lot of tweets so I can get caught up, I always have to stop to read yours and your cats' accounts. I get the biggest kick out of your sense of humor. But I also love how your writing has so much of you in it. You allow yourself to be vulnerable. We get to read about your heartaches, whether they're about a person, a place, or a pet. It's so real, so entertaining, so full of heart. Please, please, never stop writing.

Peg

This is an excellent post. I need to take some walks, I never thought about how much they do inspire writing and creativity.

Thank you so very much for this…

Wise, bittersweet and shared with my fellow Cat Writer Association members and Cat Wisdom 101 readers. Cheers to the next twenty years!

Tom Thanks for another great piece. Your writing is just superb – I keep returning to the cat books again and again as they are an oasis of joy in this sometimes screwed up/stressful world. Both hilarious and poignant in equal measure they are absolute gems. But I really enjoy all of your writing both here and on Twitter. The way you write about the countryside and folklore has encouraged me to dust off my walking boots and head into the great outdoors. I know what you mean about Twitter (to an extent)…I took a break from it for a while recently due to a reoccurrence of depression as some peoples comments started to wind me up. However after a while I decided to dip my toe back in with a stripped back version in terms of people I follow. Two of your followers who follow me took the time out to DM me to check if I was OK as they had not heard from me for a while. It was truly humbling. So as much as Twitter can be a pile of pants sometimes there is a lot of love out there for you and the felines. I'll stop rambling now and just say please never stop writing! PS Even at low points the phrase from your Guide To Countryside Dating "upside down sex behind wheelie bins" never fails to make me laugh!

Please don't stop tweeting. It's the only thing I look forward to in my Twitter feed!

Tom,

I came across you because of my lifelong love of cats, but I've grown to appreciate your skill as a wordsmith. Keep at it, please.

Rob

That was lovely. And very right. Especially liked the Velveteen Rabbit analogy. And the plumbing one. It's all good advice – I must try more walking. I'm trying to complete The Book, flailing about panicking re word count, and what you've written makes me realise I should be concentrating on the areas I'm passionate about.

Please keep on keeping on. And special thoughts for Roscoe and The Bear.

Jan x

I picked up The Good, the Bad, and the Furry at the end of 2014 after seeing a persistent number of @MYSADCAT retweets, following them to your personal Twitter account, and coming to crave more of the thoughtfulness, gentleness, and wry humor that are embodied by your tweets; it was wonderful to find that TGtBatF was (as you'd warned/promised) less about cats being cats and more about life, plus cats, countryside, and obscure folk music. I've been following this blog since news of Roscoe's recent brush with the dog and now I check every day for something new — your writing, and the things about which you write, have created a space for themselves in my heart. I love your photos of and posts about your walks through Dartmoor. My grandmother (who is also English — I'm American) used to live in Somerset, within the borders of Exmoor and just south of Minehead, but moved to the US before I grew up enough to understand just how beautiful and stirring the moors are. Your writing helps replace the lost opportunity to go tromping around looking at Very Old Things in the Fog with Free Room and Board. I'm unemployed right now, but do intend to buy your other moderately-cat-flavored books when I can and support you on this blog, because when you have the time and freedom to write what you like, the results are lovely. All the best.

Dear Tom,

As earlier comments…Also Shipley. Small and probably inadequate support here, but genuinely meant. I have 2 elderly cats myself, can relate to what you're saying. Also the book/velveteen rabbit analogy.

Very best wishes – will be in Devon in mid-March if you fancy a drink.

Jan x

Valuable advice. Thanks for sharing. We are helping to raise funds to save our community cats. Need your help to support if possible. Thank you so much. :) https://teespring.com/CatsLover

I have been reading three of your cat books aloud to my husband. You have made us laugh and you have made us sniffle quietly with your very real writing. We enjoyed The Bear,Janet, Ralph and all the other lovable characters, including the humans. We did not skip a single word of your wonderful and sometimes irreverent prose and were sad when we came to the end. We know you will continue to inspire people with your writing for a long time to come. Thank you. Time well spent. Jo

Thank you for this straight forward piece. As an artist and writer who has struggled with surviving versus creativity, I see myself in most of your comments. I have greater opportunity and focus now to continue with my artistic passion. Sometimes we just need to see someone else's perspective. Lori