- I often fantasise about having no possessions. Well, maybe not none, but the bare minimum: the amount you could easily shove into a medium-size van. The stuff you really need to get by. Plus a few nice lamps, the especially brilliant books and records. But then when you start to get into it you begin to hit a bit of a wall in your plans: there are an awful lot of especially brilliant books and records and it would appear that for around thirty years I have been on a mission to be the owner of most of them. Also, some of those lamps aren’t just any lamps: they’re quite weird or unique ones I have found at car boot sales and junk shops. I’m unlikely to find anything like them again. Are my minimalist fantasies something to do with the reality checks that middle age will inevitably bring with it? Undoubtedly. But it’s not quite that simple. I think it’s also about the semi-nomadic way I’ve spent the last decade of my life, the place I’ve reached with my work and – not least – the era we all now have to try to live in. I also really fucking love editing. And since the desires of my writing brain and my everyday brain becomes more intertangled with every year that passes, it’s not surprising that the desire to edit expands and strays from the page. But there are limits. I wouldn’t want to overedit and regret it. Three cats live here. I’ve carefully observed their behaviour and come to the conclusion that all of them are cats of the highest possible quality. They’re staying.

- Every time I move house, I fall out with my possessions, then I gradually calm down and forgive most of them but force a few of them into voluntary redundancy. You can’t relocate eighteen times in your adult life and not to some extent be alerted to the plentiful personal folly and delusion in the clutter you have accumulated: the books that you’ve now been promising yourself that you’d read for more than a decade, the shirts you like but somehow never want to wear, the records you hold onto because someone you respect told you that you should love them, the empty photo album you keep promising yourself you’ll fill, the broken laptop you can’t get back into which has some writing on it you tell yourself you’ll one day use but probably won’t, the camera whose lost rechargable battery you’ve been meaning to replace for “a couple of years” (eight). It seems a bit weird now, like looking back to the mysteries of the building of the pyramids, but back in the first decade of this century I actually owned a house. In the time since it was sold, when I faced the immense clutter that comes from staying in one fairly spacious place for almost a decade, I have done lots of things but there is also part of me that has felt like he’s done nothing but drive around the UK taking extraneous objects from his life to charity shops and recycling centres. Yet still I find more of them. Most of it is simply the result of living for a significant number of years on a planet that contains shops. I’m ambitious, in my own idiosyncratic way, but that ambition tends to be materially reflected only in new plants or old art and furniture made by dead people. If you’re like that, life will fill up even when your hand isn’t on the pump. But it can’t just keep filling up – not if you don’t have a permanent residence of your own. Siphoning becomes mandatory. You have to ask yourself some big questions. Questions like “Does another Kentia palm just represent overkill at this point?” and “Am I a record collector, or just a person strategically attempting to make money for a registered charity in the event of my death?”

- I trimmed my record collection quite severely recently. I haven’t regretted it so far, probably because I put hours of tactical thought into the process. Even now, the total number of records I own would probably strike anyone not terminally lost deep inside the magic well of music history as unnecessary. And they would be correct: it definitely isn’t necessary. I could get properly medieval on my record collection’s arse, trim it down to, say, an absolutely killer 100. I don’t think my everyday life would alter drastically for the worse. I might even find it cathartic. Most of the music would still be digitally accessible. But what a double narrative I’d lose: my own, stretching from the day in the early 1980s when my dad took me into Nottingham to a narrow, long-since-defunct shop called Revolver Records to buy ABC’s ‘Lexicon Of Love’ LP to my birthday last week, when I acquired an original pressing of The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band’s ‘Volume I’ LP, signed by the band at the 1967 Hollywood Palladium Teenage Fair. And the narrative of thousands of talented artists, some of them cruelly spat out then ground into the dirt by the sharp heel of history. I could sell them, if I got really desperate. I’d cope. But they’re nice to have around. It’s not about someone going through them after I’m gone and saying, “Wow, this weird niche commercial failure of a novelist had a mindblowing record collection.” It’s about finding a Sharon Tandy single or James Brown LP you haven’t played for a few years and the thrill of dropping the needle on it. It’s about the special joy – one that becomes more tangible every year – of holding little pieces of history in your hand.

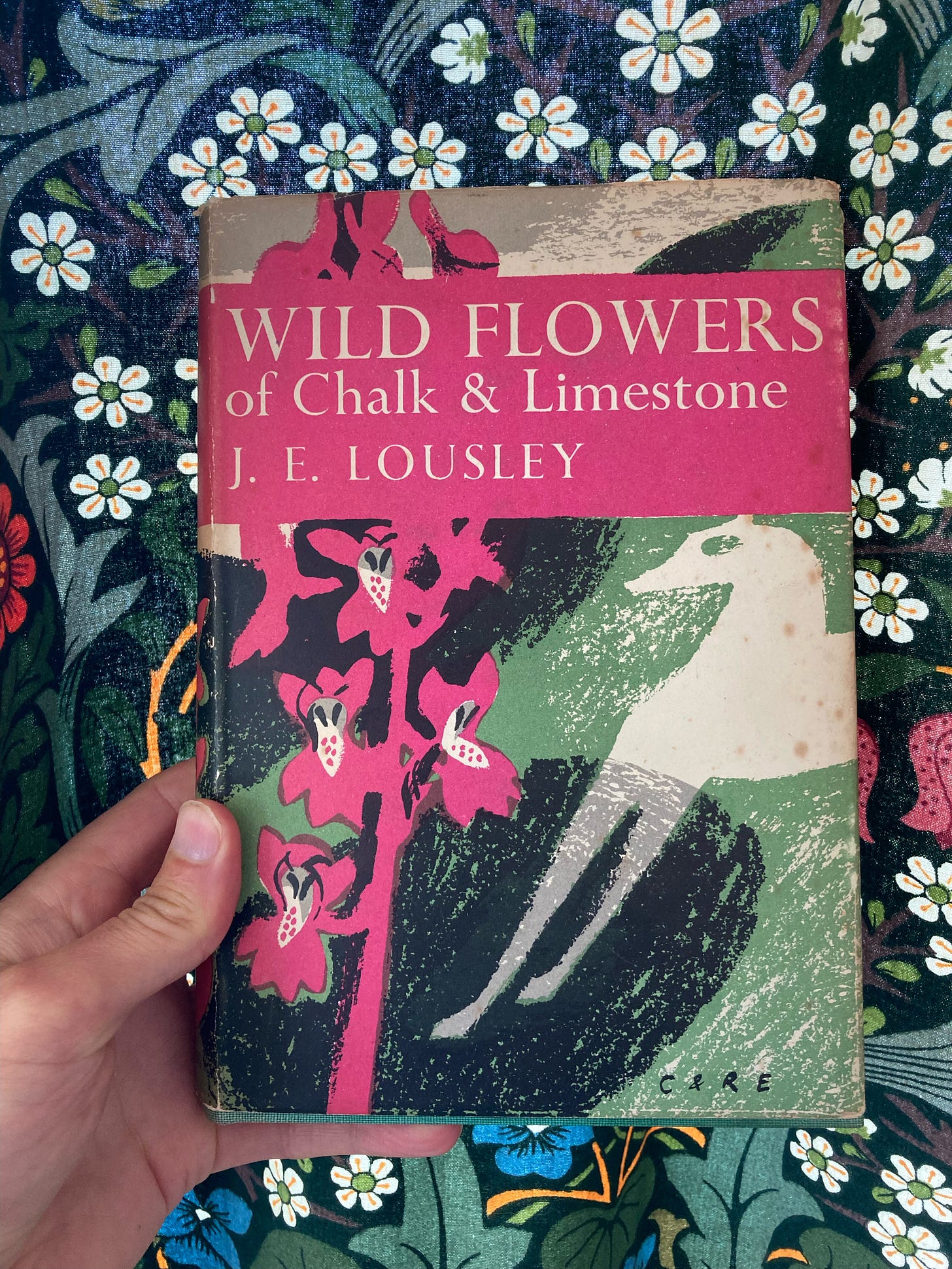

- “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful,” William Morris wrote. I’ve got around 50 editions of the New Naturalist series that Collins published during the middle of the 20th Century, and I believe the covers of these, designed by Rosemary and Clifford Ellis, to be among the most beautiful things I have ever seen. If I have reading time, I’m far more likely to devote it to a memoir or novel than hundreds of pages of dry scientific facts about pesticides or trout. I’ve read the New Naturalists on Dartmoor (1953) and Squirrels (1954) in full, and dipped into The Folklore Of Birds (1958), The Peak District (1962) and a few of the others, but in all honesty it’s doubtful I’ll read more than a couple more between now and the end of my life. If I flogged the lot, I could probably raise the money for 1/4 of a removal company for my next house move or a few weeks’ food bills, but I’ve decided they’re staying. I worked hard to find them, over a period of several years, in places where I didn’t have to pay much for them. Ultimately I probably see them more in the way I see my favourite car boot sale lamp than in the way I see my other books. This lamp was only £5 – or was it £4 – and represents a golden reward amidst many fruitless journeys to other boot fairs, and some other lamps which turned out to be a disappointment when I got them home, but it seems to get better each time I look at it and makes me happy every time I do. What you realise is very little of the time and petrol money you have expended during your hunting is logically justifiable. It would actually be more practical to go on eBay and pay significantly more for the thing you devoted all those hours to finding at a bargain price. But where is the fun in that? I want the hunt to continue. Part of the reason I edit is to not cut off the possibilities and mysteries of that hunt. I don’t want to get to the point where I see a car boot sale or shop full of old stuff and say, “I’m not going there. I don’t do that any more, because my life is sealed and complete.”

- Do you remember when everything started to change in the archive of your life? 2002 was when it first became noticeable, maybe even 2001. What was suddenly apparent was that you had messages you’d exchanged with friends – interesting messages, messages containing love or nuggets of life that you might one day want to look back on, messages that in another time would have been written in ink and saved and kept in drawers or manilla folders – on old computers that you might never retrieve, and even though you intended to, you didn’t, because suddenly everything was tumbling into the future in a new and disorientating way. Laptops and phones replaced old computers and soon they became old laptops and phones too. And then there were the photos you never stopped to edit and organise because you were busy taking more photos, and all the other new ways to send messages, which would soon be lost inside a great digital maze, and then there was something called The Cloud, which promised to keep it more organised for you, but didn’t, unless you paid it, then still didn’t, really, even then. It is the great chaos of digital clutter, the great sadness of all the intimacy and real sanely paced nostalgia for our own lives we have lost because of it, that probably makes me turn more often to my physical clutter and try to organise and archive it. It is an attempt to stand still amidst the maelstrom. I can control my physical possessions. I lost hope of controlling everything else years ago. It’s too overwhelming. Mostly, I just come to the conclusion that the best result for everyone would be if it it all vanished in one big virtual fireball.

- “Have you ever thought of living in a van?” is a question I have probably been asked at least thirty times over the last half decade. The people who ask me it are always people who know I’ve moved house a lot but don’t actually know me much beyond that, because if they did, they’d probably know what an aesthetically finicky homebody I am. I don’t travel light. I like pottery and hot baths. When I search my soul I find that I am no less interested in filling a living room with the kind of giant floor cushions Habitat sold in 1972 than I am in exploring the thinly populated forests of the world. That these days I live with a fellow homebody who also doesn’t travel light makes living on wheels, or a narrowboat, even less of a viable option. It actually gives me more of a desire for stillness, more of a yearning to get away from the uncertainty of renting. Love can alter your view of possessions. We talk about living more simplistically. The dominant line of thinking becomes, “As long as there’s us and our animal companions, nothing else matters.” But I notice we still own original pressings of all the first six Doors albums, even ‘The Soft Parade’.

- For most of 1994, 1993 and the last half of 1992, when I was in the final part of my teens, I almost exclusively wore band t-shirts. If you chose to wear a plain top instead, there was always the terrible worry that any stranger who saw you walk past them on the street might not know that you loved The Lemonheads or Guided By Voices or The Breeders and make the mistake of thinking you were just a person. I still wear band t-shirts every now and again. I have a Linda Ronstadt t-shirt that’s made of extremely comfortable fabric (ok, there’s no point skirting around the truth here: I have three Linda Ronstadt t-shirts that are made of extremely comfortable fabric). But also it’s nice to sometimes get chatting to a fellow Linda Ronstadt fan on the days when I wear it. I see a more subtle but similar pattern in the way I’ve set up houses over the years: it become less about trying to say anything to the world, more about daily comfort and pleasure. The books I choose to keep are for me but if someone visits and spots one of them that they’ve read and wants to chat about it, that’s great. The sofa that was quite unpleasant to sit on but looked cool and prompted friends who slept on it after parties to remark on its weirdly comfortable qualities as a bed has long since been sold. It’s been many years since the books on my shelf were as much about impressing mysterious judgemental and intelligent strangers I’d invented in my head as they were about my actual reading habits. What’s there is largely an accurate measure of what I’ve loved in the past, what I love to look at (those New Naturalists) and what I am genuinely excited about reading in the future. The person they’re there to impress is me. When life was filling up a little too fast, between 2016 and 2020, as I planned and wrote my latest book – the big one that I’d always been wanting to write – I looked at my shelves, and they helped motivate me. What was there was some of the ingredients to the soup that my book would be: the ones that, with my own internal stick blender, I’d mix with my hopes and disappointments and experiences and opinions and all the people I’d met and places I’d been and stories I’d heard. Of course, I bought too many ingredients, and there was no possible way I could fit all of them in. But that’s the way I prefer to go about things: overdo it, then get honest and strip it back to the essentials. But where do you stop, with that stripping down? That often feels like the big question. Perhaps it doesn’t matter as much as we often convince ourselves it will. After you’re done, you will probably still be alive, and you’re still going to arrive at the realisation that you’re just a person.

You can now subscribe to my Substack page here.

A timely post for me to read. I am in the process of decluttering and stripping down 30 years of living in one house with 8 children and odds and ends of inherited objects in anticipation of retiring in another country. Your observations about the importance of possessions – mirroring my own – helped with making some decisions easier to make. Now, back to gleaning the most meaningful and loved objects from the others.