One of the many ways that the internet is cruel and annoying in a “pissing down your back and telling you it’s raining” way is that, at the very same time as ruining people’s attention spans and preventing them from concentrating properly on books, it is constantly reminding us that we are not reading enough and showing us what a vast amount of reading everyone else is getting through. You regularly see the book piles of strangers, especially on Instagram, twenty or thirty high, with captions such as “This is what I got through just during last Thursday afternoon between yoga and going out for a meal with James to discuss our honeymoon plans.” Some of the people making these claims even have full-time jobs and families. “How do they do it?” you wonder, thinking about the novel you have just finally finished, after four weeks of squeezing eleven pages of it in here and there during baths and short train journeys. I am far less bothered by this than I used to be: I’m more interested in reading a book than havingread a book and increasingly at peace with being a slower-than-average reader. But sometimes it is nice to read something a little shorter and simpler to get back into that reading groove. With this in mind, I recently reread some of the 1960s and 1970s editions of Ladybird’s Well-Loved Tales series. My progress was instantly amazing, every bit a match for the most boastful Bookstagrammer, yet I was also very much lost in the universe created by Ladybird directly before my birth, paying full attention to both Vera Southgate’s narratives and the magical, often very unsettling illustrations by Robert Lumley and Eric Winter. I smashed through 1972’s The Big Pancake in the brief gap between being signed in by the receptionist at my local Doctor’s Surgery and being called to see the doctor himself then polished off Little Red Riding Hood and Dick Whittington while waiting for a cauliflower and kale curry to simmer to its apex. I’ve read ten of them now, in under a week, and while I certainly had an advantage in having read them before, books can be very different at different times in your life, and I thought it might be fun to report here on a few of my findings, after over four decades away from this particularly folksy and rustic part of the the Ladybird backlist. (Please note: contains spoilers.)

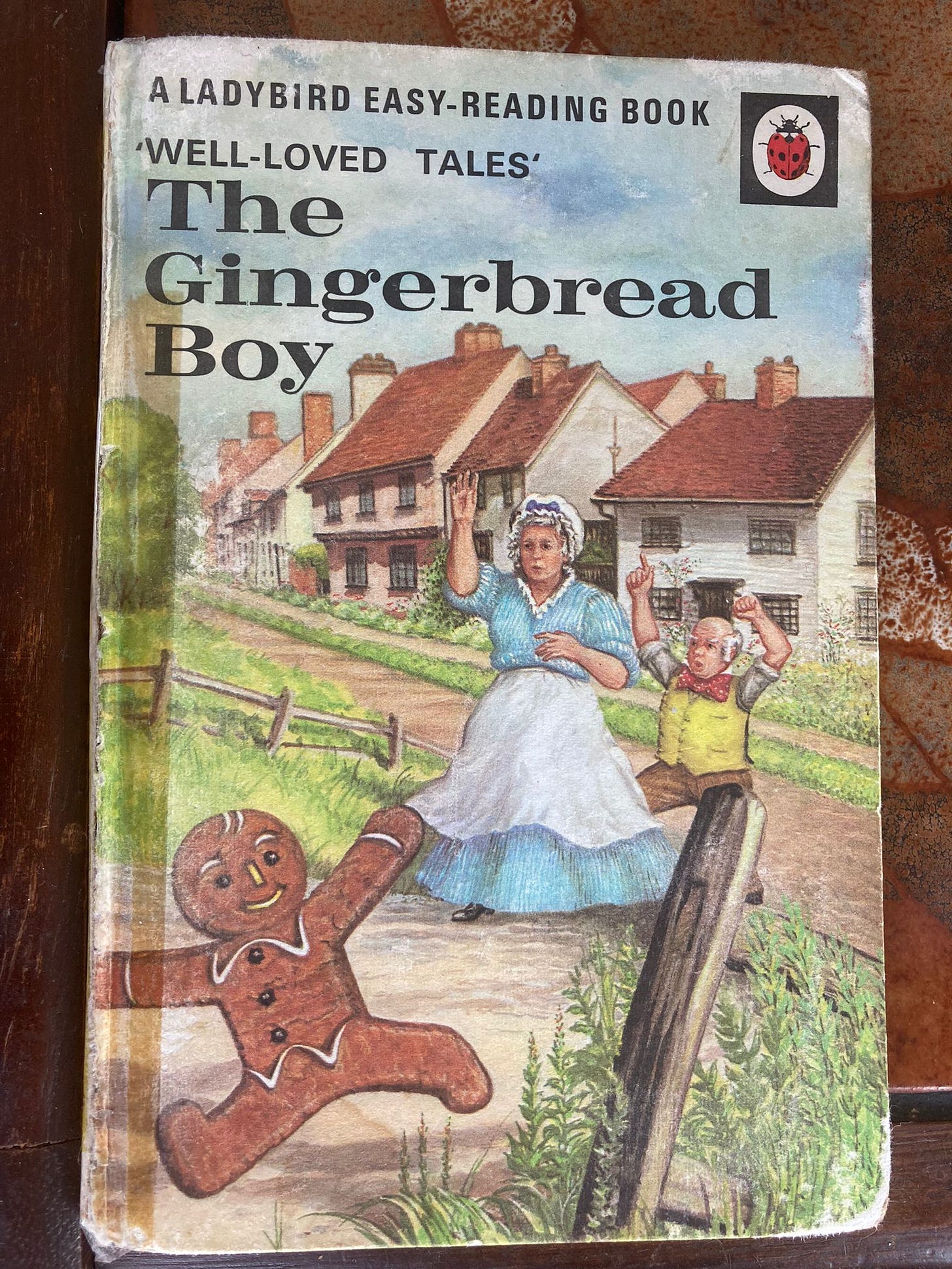

THE GINGERBREAD BOY

Maybe not quite the the most folk horror of all the Well-Loved Tales, but surely possessing the most folk horror cover, darkness springing from its every corner. For example:

- At least one of those cottages in the background has to be seriously haunted

- What has the nasty little syrup-based fucker just been up to?

- Palpable aura of marital unrest.

- Posionous/possibly hallucinogenic weeds in the foreground.

- Face in the tree in the background, and the fence post.

- Looks bucolic but you just know it’s the fashion in which they’ve framed it and there’s some godawful executive new builds just out of shot, which some evil property developer bulldozed a few badger setts and hedgehog homes while constructing. Probably some torn-up porn mags in the woods behind that spooky tree, too.

- What are the buttons on the Gingerbread Boy’s invisible shirt made of? They don’t quite seem to be chocolate or raisins. Could they in fact be the eyes of his victims?

My favourite moment in the book is when, after perplexing humans, cattle and horses with his antics, probably while high on food containing artificial additives, the Gingerbread Boy gets a lift across a river while balancing on a fox’s nose. The image is highly psychedelic and would 100% seduce me into taking a punt on the work of a straight ahead pop band from 1966 who used this image on the cover of an LP they made slightly later after their aesthetic took a darker, more layered turn. While the harmony it shows between Gingerbread Boy and fox is transient, being shattered only a page later when the fox flips the Gingerbread Boy in the air and swallows him, I think it’s most productive not to focus on how tragically the friendship of the two ended, but on just how perfectly balanced and aesthetically appealing it was for that one brief swim they took together.

Incidentally, one of the houses depicted on the cover – in Cage End, Hertfordshire – where the Gingerbread Boy might or might not have briefly lived is currently for sale for 1.35 million with Knight Frank estate agents. I’m not overly keen – and feel sure The Gingerbread Boy’s disatisfied adoptive mother and father would be, either – on what they’ve done to the kitchen.

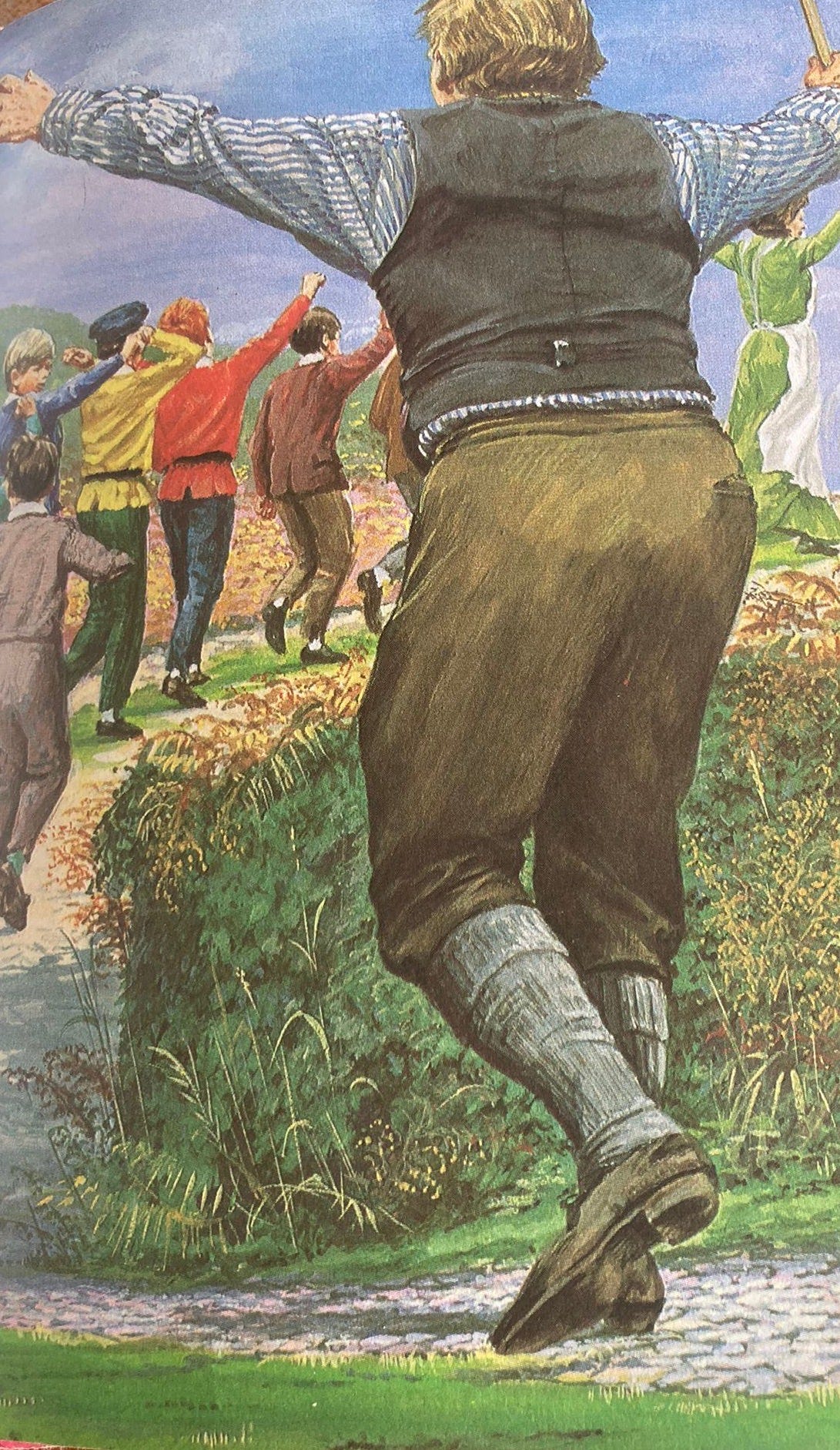

THE BIG PANCAKE

The Monkees had some very good songs of their own, some of which were very weird in entirely their own way, and it’s wrong to think of them as merely a corporate, manufactured copy of the Beatles. Similarly, it’s unfair and short-sighted to think of The Big Pancake as just a reworking of The Gingerbread Boy owing to the fact that it reuses the “conga of animals and humans chasing some food through idylllic yet Pagan countryside” motif. Here, the central food “character” is more abstract – fundamentally just a faceless alien blob with uncanny powers of rolling, belying its non-aerodynamic shape – and a musical element is more apparent than in the other book. As a mother and her overwhelmingly large brood of male children, all of whom look a little like Victorian ghosts, chase through their village and its edgelands the generous pancake she has made for them, it is hard not to speculate regarding what the song is that they are all dancing to. Could it be a song by the then-just-coming-into-their-prime Funkadelic? Sonny And Cher’s ‘The Beat Goes On’? Or are they in fact listening to ‘Miri It Is’, the haunting 13th Century tune which soundtracks the ill-fated procession towards the cliffs in The Wicker Man?

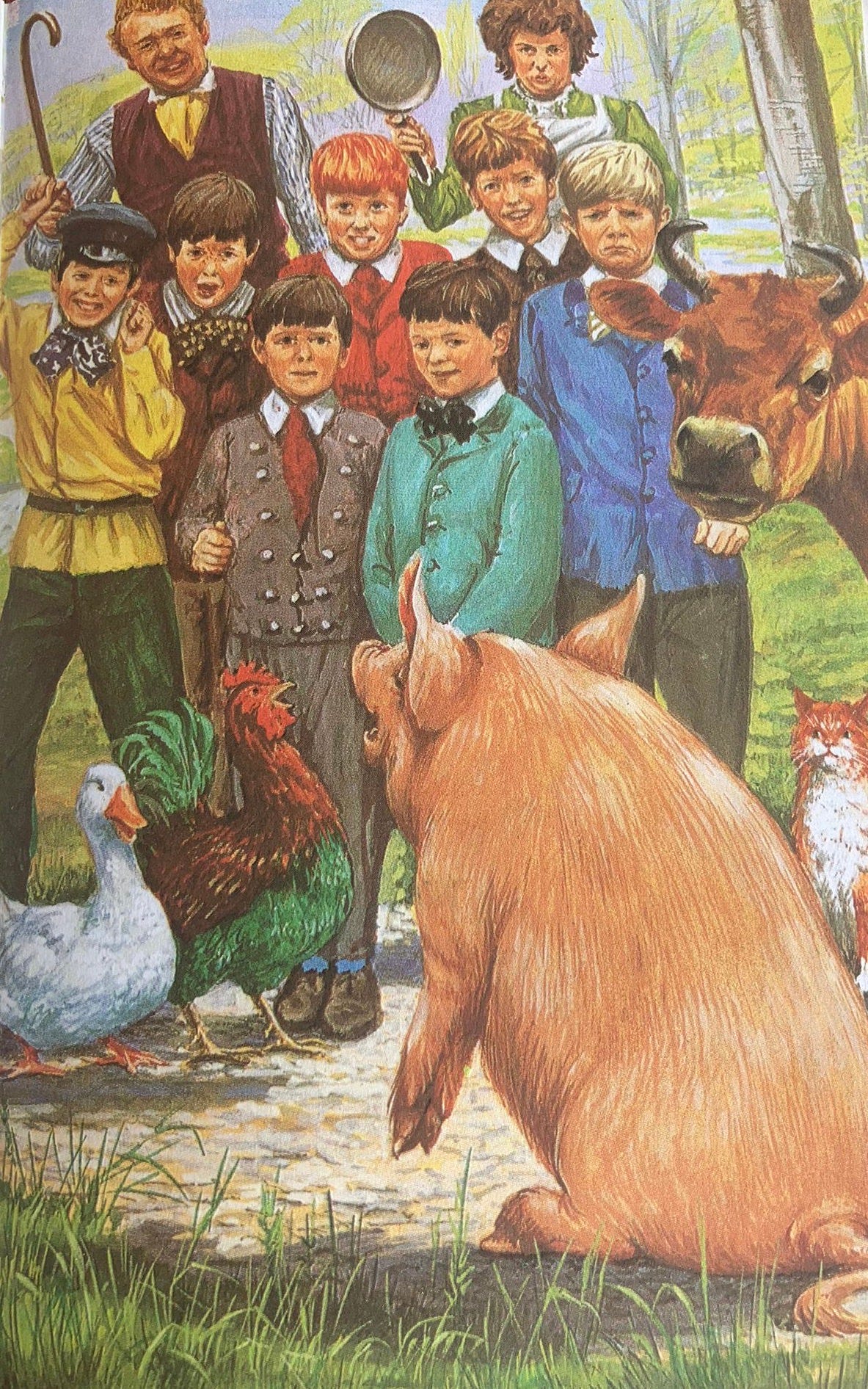

My feeling is that prominence of the cockerel on the cover is an oversell to cockerel enthusiasts since he plays a fairly minor role in the rustic conga: he is certainly nothing like as much of a significant character as the upper class man in plus fours who joins in the fun on page 26, apparently solely because, while on the back nine of a nearby golf course, he has come to the realisation that golf is a pointless game which can never truly lead to a fulfilled life. When the pancake is finally eaten by a pig, the man – along with the cockerel – is one of the few onlookers who seem amused by it. The spoiled slightly Boris Johnsonlike Victorian ghost child on the far right looks especially ruffled by the pig’s gluttony, the ginger cat seems on the verge of tears and, from the look on the mother’s face and the way she is gripping her frying pan, it is clear that even in this darkish era for fairy tales, Ladybird has decided to spare us the more gruesome alternative ending where she beats the shit out of the pig and the upper class man and the cockerel strive hopelessly to pull her off him, shouting “Leave it, Janet! He’s not worth it.” I can’t really tell what the cow is thinking. I get the impression it is mentally elsewhere.

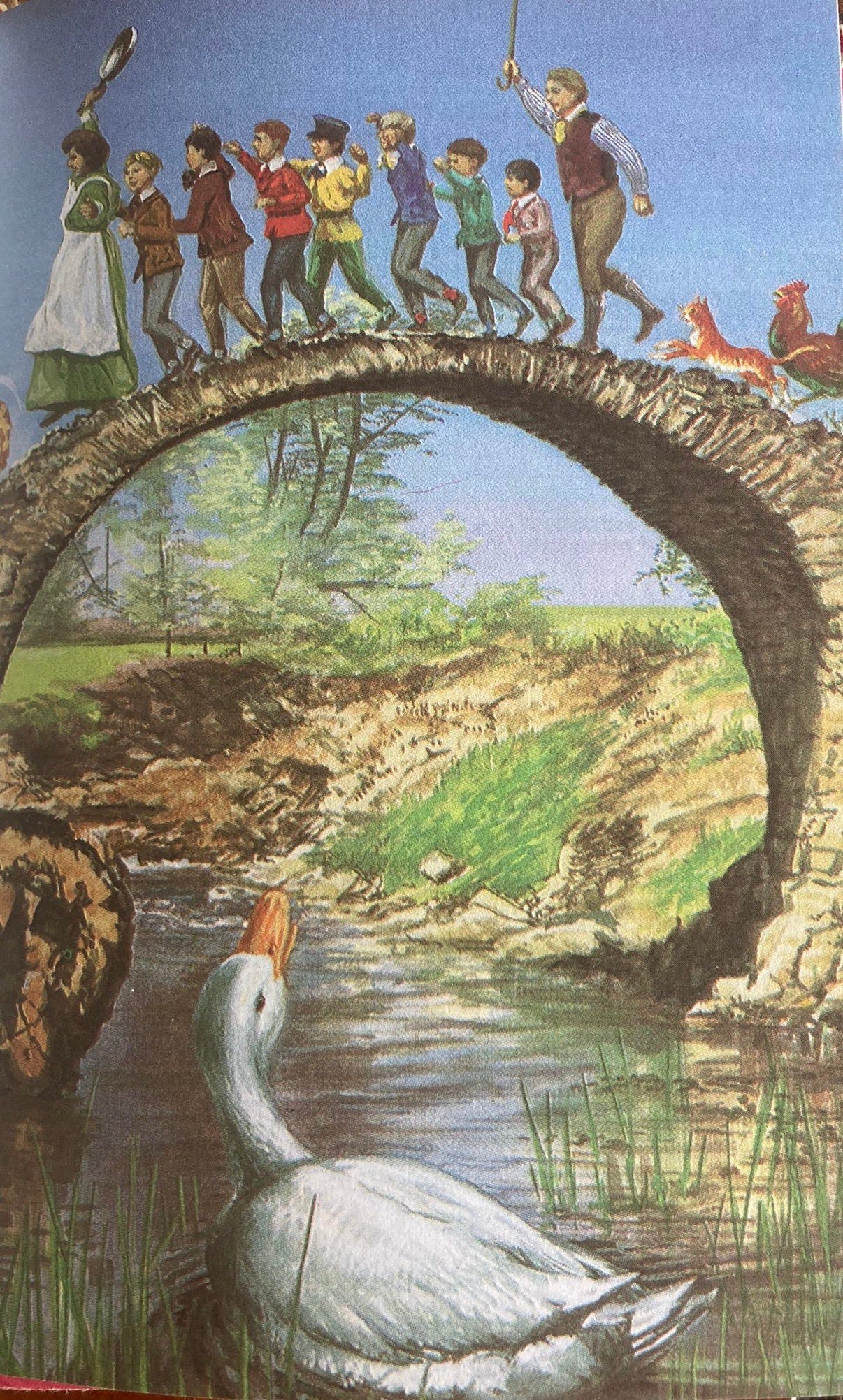

I like the dummy Vera Southgate and Robert Lumley sell readers who have already enjoyed The Gingerbread Boy, where the pig balances the pancake on his snout and we wonder for a moment if he is going to swim across a natural body of water with it in a false gesture of kindness and friendship, but I think my favourite illustration of all is the one a few pages earlier, where the conga passes over a hyper-real version of a medieval Dartmoor clapper bridge. Without wishing to be a West Country pedant, though, I do think the river looks less like a one of the many you’ll find on Dartmoor and more like one of those you might find closer to the Dorset border: perhaps the lower reaches of the Otter, somewhere between Tipton St John and Ottery St Mary.

Once again, the phantom of music seems apparent during the retelling of this universal tale of duplicity. What is playing while the wolf leads Red through the wildflowers on a beautiful spring day? I am getting a strong vibe of ‘Windy’ by The Association but it could just as easily be ‘Some Velvet Morning’ by Lee Hazlewood and Nancy Sinatra. The wolf could have made everything so much simpler by just eating her then and there, but instead concocts his elaborate ruse, possibly more for the historical fame than the sustenance. Sorry to be a naysayer here and I know these times, whenever they actually happened to be, were less sceptical ones, but Red looks at least nine and a half here and there is no way on earth she would have actually fallen for the wolf’s disguise. Could he not have at least tucked both his ears into her nan’s bonnet?

After Red’s dad rescues her and her nan from the wolf’s stomach, the innards clean off remarkably well. Her dad has a look of Rock Hudson in the 1955 Douglas Sirk film All That Heaven Allows. I would like to read the sequel to Little Red Riding Hood where he faces up to the true nature of his sexuality and, after inheriting Red’s nan’s cottage after her death, shacks up with a fellow male woodcutter and the two of them go into business together, with Red – having forgiven him for leaving her mum – initially manning the phones for them then gradually taking over the corporate side of the enterprise, which, while giving her the wealth she desires and enabling her to buy all the smart capes she had ever wanted, never quite makes her happy or removes the taint of slaughter from the cottage’s main bedroom, leading her to sell the property in summer 2020 at the height of pandemic-influenced rural panic mortgaging and make a tidy profit, despite the building’s lack of vehicular access, yet still not exorcise the nagging guilt embedded deep inside her that she had once been at least partially responsible for the death of a wolf who, for all his faults, was essentially just going about his natural business of being a wolf.

DICK WHITTINGTON AND HIS CAT

The setting for this story of a poor boy on the make is the late 1300s but in another sense it is a product of the time of its publication, being very 1966 in some ways. With his slightly Small Faces/Herman’s Hermits hair and what is a quite remarkably large selection of kaftans and jeggings for someone on the breadline, Dick has the look of one of those musicians of the British Invasion who, as the hippie era hit, began to move in a more acid folk direction, allowing his songwriting to soak up the influences of Aleister Crowley and Frazer’s The Golden Bough. I enjoyed the look of London here, its half-timbered buildings and cobbled streets, but I have to confess that this was definitely not my favourite of the Well-Loved Tales, either as a child, or on my recent reread.

The thrust of the narrative is that by sending his cat to a nameless foreign land full of ethnic stereotypes, where the cat kills lots of rodents, Whittington – by this time clearly no longer making music of any vitality or relevance – becomes the wealthy Lord Mayor of London. But there are holes in the story everywhere. Why does he stop looking like Steve Marriott and instead come to resemble Henry VIII? What precisely were the marks power left on him in the interim? What happened to his cat, who he clearly once adored? How did he feel about selling it, as if it was merely a commodity to use to trade up in life, rather than a faithful living being with an emotional life of its own? Did the guilt actually kill the talented, innocent, animal-loving pop musician he once was? Readers of her later books, who have come to expect more of her, will probably suspect Vera Southgate was obviously still very much finding – or even searching chaotically for – her feet as a story reteller here.

THE MAGIC PORRIDGE POT

There is soooo much going on here, nearly all of it wonderful, and seriously pushing the envelope of what a children’s tale can be. Firstly: the porridge itself, laced with LSD, with its ever-present pink halo. Not only does it provide unlimited food for the poor but, if you look closely, it enhances the life of smaller creatures of the locality immeasurably. By the end, mice everywhere are tripping their whiskers off, sailing around on porridge bowl boats, and a grasshopper and a caterpillar have started creatively bouncing off one another and formed an anarchic arts collective. There are stories within stories here and it’s not as if the main one isn’t great enough on its own: that of a town which, due to a mother’s ailing short term memory, becomes totally covered in porridge. The final frame, where a porridge hill has raised the settlement above the remainder of the landscape, reminds me a little of the hyper real Gloucestershire depicted in the paintings Kit Williams did not long after this for his brilliant Masquerade. I am also a big fan of the cape worn by the mysterious old woman who first introduces us to the porridge pot, which might well be the best cape of all in a genre where there is no shortage of competition.

THE SLY FOX AND THE LITTLE RED HEN and THE WOLF AND THE SEVEN LITTLE KIDS

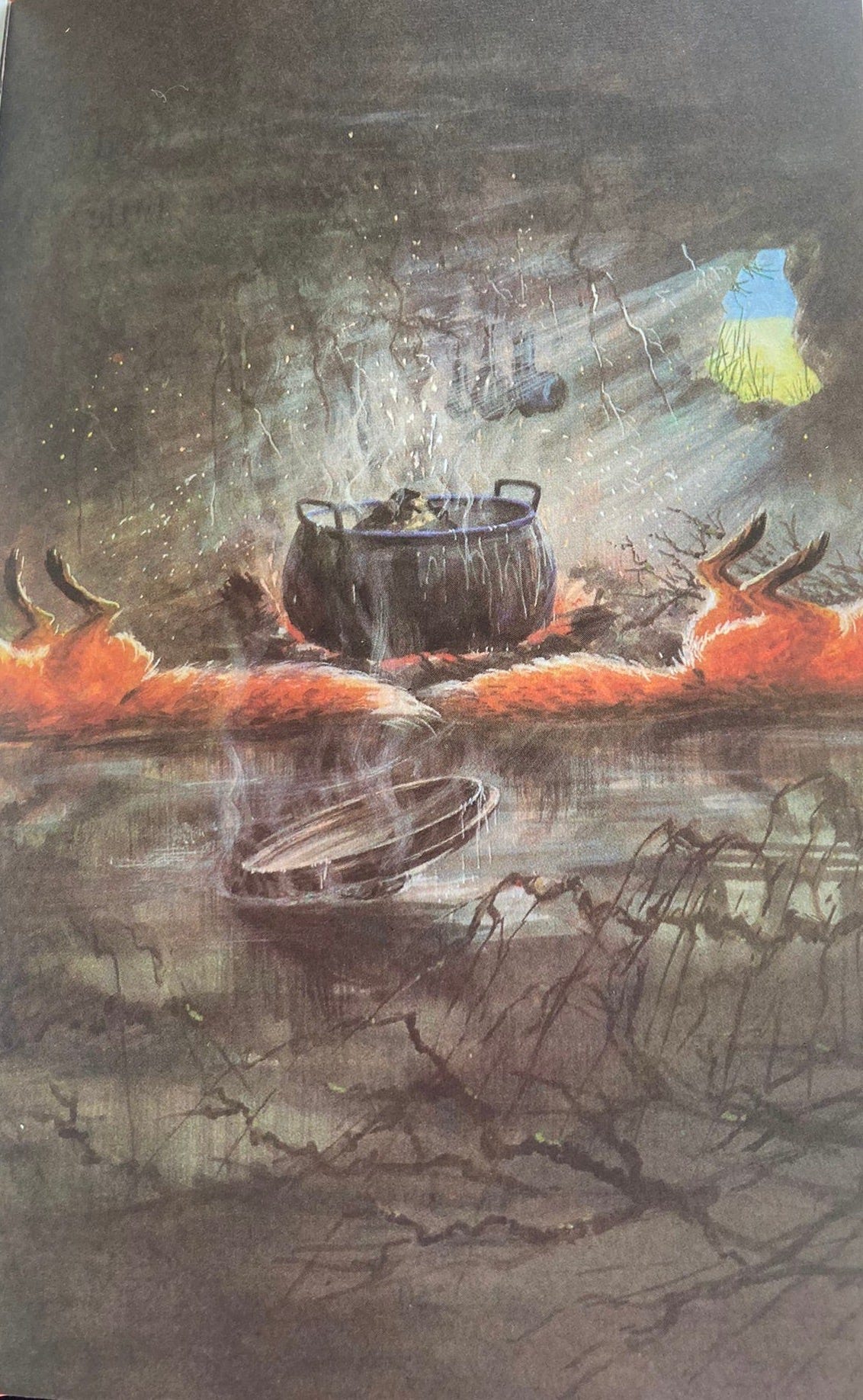

I will say this for the Ladybird Well-Loved Tales of the late 1960s and early 1970s: there is something very “equal opportunities” about them, in terms of the fates of predator and prey. In The Gingerbread Man, the fox got the meal he wanted and walked away happy, but in the breathtakingly dark conclusion to The Sly Fox And The Little Red Hen, a young fox, having been outwitted by a hefty house-proud chicken, pours heavy stones into a pot of boiling water and scalds himself and his mother to instant death. It is hard to decide whether this is even more brutal than the finale to 1969’s The Wolf And The Seven Little Kids, possibly the most unforgettable of all the Well-Loved Tales, where the wolf, having had stones sewn into his stomach by a vengeful mummy goat, falls into a well and drowns.

This, I realised upon my reread, was the Ladybird book that most deeply and permanently embedded itself into my psyche as an infant. I found the wolf in Red Riding Hood frightening but it was multiple versions of the more salivating, deranged one here which I saw when I used to have recurring nightmares where resolute lupine armies advanced from the foot of my bed to devour me. It is also undoubtedly why wells terrified me for the rest of my childhood and still, to an extent, do. Again, there is so much going on here. The book answers the questions it needs to, but also leaves a few hanging, in a successful way that just makes it stick with you all the more. Some of the latter include “How did the wolf remain in his deep sleep while the goat cut open his stomach to remove her children, then resealed it?”, “Why are caterpillars so constantly emotionally moved by everything?” and “Who did the surprisingly tasteful upcycling job on the clockcase the one undevoured kid manages to hide in?” I defy even the most robust child to read this and ever banish from their mind the image of the wolf, his stitched stomach pregnant with rocks, staggering dehydrated down the footpath towards the well, tongue lolling, red eyes suggestive of three sleepless weeks on vodka and barbiturates. As for the excellent cover, I can’t beat the description of it by a man called Craig who follows me on Twitter: “A lovely scene of a family imploring Satan to break their enemy’s legs through the medium of chant.”

My latest book, Villager, is published in paperback next week. You can pre-order a copy direct from my publisher here, or with free worldwide delivery from Blackwells here. You can subscribe to my Substack page here.

I remember the Gingerbread Boy and The Big Pancake book covers very well. My recall of the content was a little hazy before you reminded me of the detail. All I could remember were scenes of marching villagers in both, somewhat reminding me of scenes from The Wickerman or The Hunchback of Notre Dame, minus a pitchfork or two. They really were dark, weren’t they. The one I would add would be the Three Billy Goats Gruff. Weeks of possible nightmares contained in those pages!