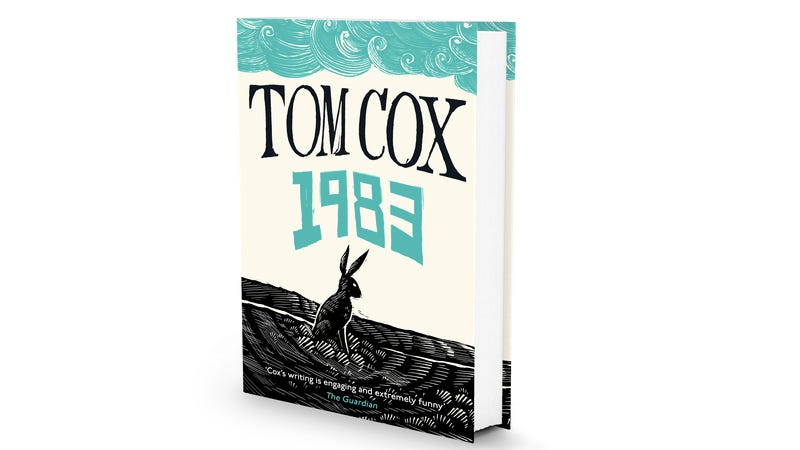

My big news today is that I’m writing and crowdfunding a new novel. It’s very different to my last one, but that tends to be what happens with my books, since I’m restless like that: I have had a habit, both in my recent writing and my recent life, of not staying long in one place. In my previous book, Villager, I was in a fictional moorland village on the UK’s south-west peninsula, living its folklore and landscape and ghosts through the eyes of almost two centuries’ worth of characters, almost all of them human. In this new one, I have found myself somewhere not very much like that at all: amidst the spoil heaps and chip shops and Miners’ Welfares of Nottinghamshire, the last industrially bruised outpost of the Midlands before Northern England begins. The timescale is an even bigger contrast: I’m planning to be there for no longer than twelve months. But it’s a very good twelve months. Or it was, for me, when I lived the real version of it, in the same place; I’d even go so far as to call it one of the happiest parts of my life. I’m already enjoying writing my reworked, semi-autobiographical version of it arguably as much. I have decided to publish it with Unbound, just like my previous five books, because I love the way that they give you, my readers, more chance to be involved, and I know that no other publisher would make it look more lovely or give me the opportunity to write it with more freedom or more of the non-commercial, non-branded weirdness I know it requires to be the best book it can be.

Why have I yearned, even ached, so much to write about 1983 lately? On a purely nostalgia-based level, I find myself wanting to swim around in a time from my life when there was a bit more idle space in the world: a time when I went to a lovely school, had a fertile imagination, a great social life and spent a lot of time outdoors. But there’s much more to it than that. I turned eight midway through 1983, and in a way it seems like the first year of my life for which my memories are solid and fully coloured in, an energetic midpoint of childhood when, fully recovered from the illness that had almost killed me a couple of years earlier, I started to properly become the me I am now. 1983 – a general election year, and the eve of the Miners’ Strike – also seems, in retrospect, to be when the big lights of the 1980s, Thatcher’s 1980s, fully came on, when things started to get a little glossier and, in many ways, more problematic. Nottinghamshire – a very unglossy place, halfway up the country, with its strong reliance on the coal industry – seems to me an interesting prism to examine this through. A pit village in north Nottinghamshire, quite a lot like the one I grew up in, especially.

You can’t avoid politics when you write about a place like this at a time like that, but I also would not describe 1983 as a political novel. It is also definitely not a ‘Hey, remember ZX81s and C5s – what was all that about?’ pop-cultural cheeseboard. It’s a story about an ordinary family, in an ordinary village sandwiched between two ordinary collieries, an ordinary childhood, an ordinary (yet unusual and magical) inner-city primary school, an ordinary(-ish) robot maker, and some extraordinary goings-on. It’s very autobiographical and very unautobiographical, mundane and sci-fi, silly and serious. But it is also marinated, unavoidably, in the cultural atmosphere of the time. If you want a flavour of what D. H. Lawrence country had become by the time ‘Blue Monday’ was first on the playlist at the local leisure centre roller disco, you’ll inevitably find out here.

The idea for all of it came from me thinking about the year of my birth, and precisely how being born at that time in a middling, slightly grim sort of place contributes to the construction of a person, then by extension thinking about a book published during that same year when I came into the world – E. L. Doctorow’s masterpiece Ragtime– and whether I could do for the early 1980s something not entirely dissimilar to what that novel did for the early 1900s. ‘’Ark at ’im… Thinks he’s E. L. Fucking Doctorow!’ I can hear a Nottinghamshire voice – the one permanently situated in my head that forever chides me for having ideas above my station – saying, as I confess this. I don’t. I like him a lot but I think I’m me. Also, since I formulated that vague ambition, 1983 has become something else, something slightly off to the side. It was always going to: I’m writing it, and that’s what happens when I write things.

I sometimes forget that in a pre-smartphone age, most people didn’t take a lot of photos of their everyday life. My family did, and I am thankful for that, especially as I get further into the researching and writing of 1983. As I go through my mum and dad’s old albums, I fall down holes in time, and little cupboard doors that have been closed for years creak open, revealing more about the way my life once was: innate events that are part of me but nonetheless seem revelatory as they return. My memory for this period is weirdly great – better than my memory for many periods considerably later than it – and now, with the photos opening those cupboard doors, it’s even more high-definition. But from all this emerges a Nottinghamshire universe slightly skewwhiff, not quite the one I lived in, but one I believe in increasingly wholeheartedly. I can smell the stale fag smoke on the top deck of the bus, hear the shouts of ‘geroff!’ and ‘mard arse!’, feel the click of the red plastic clasp on my Darth Vader lunchbox with that day’s snap inside (I hope my mum packed a Jacob’s Club and hope even harder that it’s a mint one), see the turn of the headstocks – great dystopian wheels in the sky – in the distance, behind the house. They have appeared to me many times, in dreams, as time has gone on. There’s something odd about them, something not quite of this world, something distinctly ‘other’ about this place that even after all these years – the same number of years that separate the time of this book’s narrative from the middle of the Second World War – I don’t quite understand, but want to, very much. And that’s why I can’t wait to write more.

You can pre-order and contribute to the crowdfunding of 1983 here via the Unbound website. If you go to the bottom of the page, you can also read a small extract. There are also some nice limited pledge rewards, including a handmade scarf just like the one I’m wearing at the top of this page. (Publication will be in spring 2024.)

Pre-ordered, just discovered your work! What is the best way to acquire your books in the USA as far as profits to you go?

Thank you, Jeffrey! And I really appreciate you thinking of this. The best way is probably via an independent bookseller over here but that will mean big postage costs for you. I am very happy with people ordering from Blackwells (now sadly no longer independent and owned by Waterstones) and as far as I know they are still doing worldwide delivery… https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/9781800182370?gC=5a105e8b&gclid=CjwKCAjwq4imBhBQEiwA9Nx1BrJM5JdF1h8VOtCbBXEHGytoOhENwkfAUoNCPDJHPNcv8R_0pxM20hoC_p8QAvD_BwE